Muscle fiber type is one of those topics on which people love to make uninformed statements. You may have heard things like, "Heavy weights work those slow twitch fibers." Or "You have to do plyometrics to target quick twitch muscle." Another claim I recall reading as a teenager is that your number of fast twitch fibers is completely genetic and cannot be changed. This is flat out false. Muscle fiber type is adaptable, and this is something that should definitely be taken into consideration in training for explosive athletic performance. Before getting into that, let's do a quick overview of muscle fiber types. Slow twitch fibers produce less tension and take more time to reach peak tension but possess excellent endurance. Fast twitch fibers produce greater tension and reach peak tension more quickly but have very little endurance. Having more slow twitch fibers is helpful for low effort endurance activities. On the other hand, possessing a higher percentage of fast twitch fibers is advantageous for any activity that involves maximum force production such as sprinting, jumping, and yes, heavy lifting. Because heavy strength training features the highest muscle tension, it's actually a fast twitch dominant activity. There is a continuum of fiber types from slow to fast, but we have classified them into three primary types, Type 1 (slow), Type 2A (semi-fast), and Type 2B (fast). A muscle fiber's type is identified by the chemical composition of the head of the myosin protein molecules within the fiber. Myosin heavy chain I, IIA, and IIX are associated with type 1, type 2A, and type 2B fibers respectively. The behavior of the fiber is also influenced by the neuron that activates it. We don't have this relationship totally figured out yet.

|

| SKELETAL MUSCLE FIBERS |

Fiber twitch speed is adaptable. It is shaped by activity over time. People may expect this to simply mean that endurance activities yield more slow twitch fibers and high force activities yield more fast twitch fibers. And this does appear to be true if we just compare endurance athletes and strength athletes for example. However when we look at sedentary people, we find that they tend to have more fast twitch fibers than anybody. The graph below shows average fiber type distribution among a small group of runners, strength athletes, and sedentary people. The full study is here: Human Skeletal Muscle Fiber Type Adaptability.... What this tells us is that a need for greater force production is not the defining stimulus that influences muscle fiber type changes. Rather it is a need for endurance. Sedentary people have no need for endurance, so their muscle fibers default toward being fast twitch.

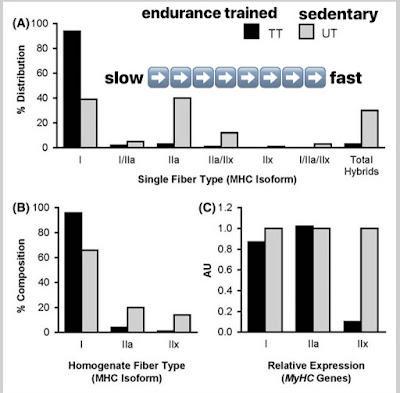

Skeptics of fiber type changes may suggest that the differences between athletes in different sports exist at birth and cause each person to naturally excel in the sport they end up pursuing. While genetics certainly do influence muscle fiber types, a high level of adaptability is clearly evident. In fact the next study examined numerous drastic differences, including in fiber types, between genetically identical people with very different histories of exercise. Muscle Health and Performance in Monozygotic Twins... The graphs below show the major differences in fiber type distribution that developed over time between the sedentary and endurance trained twin. You can see that over time the endurance activity lead to far more slow twitch fibers compared to being sedentary. This makes sense.

The next piece of evidence is a bit counterintuitive. Rapid Switch-off of the Human Myosin Heavy Chain IIX Gene... In this study sedentary subjects performed just two consecutive days of strength training. In the days following, the gene for myosin IIX (the fastest one) shut off, so to speak. This does not mean that the fibers converted to type 2A already in four days. The actual changes to the protein molecules would have followed later. But the key point here is strength training, even though it is fast twitch dominant, actually caused a shift toward slower twitch speed compared to being sedentary. Now let's be clear. This does not mean that these research subjects would get less athletic from strength training. If they combined some sort of athletic activity with strength training, most likely the gains in neuromuscular strength would far outweigh the influence of type 2B fibers shifting to type 2A. In that scenario these subjects would see drastic improvement in athletic measures. But we still need to make note of the influence of strength training on fiber type.

Next we come to one of my favorite topics in all of sports training, the overshoot phenomenon. The research: Myosin Heavy Chain IIX Overshoot... Again sedentary subjects performed heavy resistance training, this time for three months. At the end of the training, many of the myosin IIX molecules had converted to myosin IIA. This lines up with the results from the previous study. But then the subjects returned to being sedentary, and after three months of detraining myosin IIX content had shot up well beyond the initial level (graph below). This is known as the overshoot phenomenon. Again let's be clear. This does not mean that the subjects were more athletic after three months of detraining. The drastic loss of neuromuscular strength from long term inactivity far outweighs the fiber type changes. The overshoot phenomenon refers specifically to the increase in myosin IIX content. It does not refer to an increase in athleticism. Muscle fiber type is just one factor in athleticism.

The overshoot phenomenon was replicated in this study: Changes in the human muscle force-velocity relationship in response to resistance training and subsequent detraining. Again subjects did three months of resistance training followed by three months of de-training, which produced a loss and then overshoot of myosin IIX content. This study also used several performance measurements of knee extension at different speeds. The de-training resulted in a loss of strength gains in resisted knee extension as expected, but this was accompanied by clear enhancements of unloaded knee extension as measured by acceleration, velocity, force and power at high velocity, and rate of force development. The influence of the fast twitch overshoot is obvious.APPLICATION: LESS IS MORE

What understanding can we establish from the overshoot phenomenon and the other research? And how can we harness this information to improve training for athletic performance? The key principle to understand is that when muscle fibers are rested, they default toward the fast-twitch end of the spectrum. All activity pulls fibers away from the fast-twitch end, but how far away depends on the nature and volume of the activity. This has practical applications to training.- A lower activity level promotes higher twitch speed. That supports the "less is more" concept. Instead of joining "team no days off," try doing three good workouts per week. Instead of spending five hours on the basketball court, maybe do one high quality hour. It may be necessary to take on a more rigorous training schedule for a while; at some point you will want to balance that out with more rest to reap the benefits of all the work.

- Avoid endurance work and conditioning whenever possible. There is no reason you need to be in peak cardiovascular shape in the off-season. When conditioning is necessary, don't overdo it. The best way to condition is to match the demands of your sport as closely as possible. That means a lot of athletes should be able to develop the necessary fitness level just by playing their sport.

- After you have strung together several weeks or months of consistent hard training, you will most likely benefit from an easy period. This is getting beyond just fiber types and into other topics like fatigue of the nervous and endocrine systems. Of course those things very well may be all connected. But anyway the easy period may be an easy week after a few hard weeks, or it may be an easy month after a few hard months. The goal during this time is to have a low physical stress level to allow recovery while still maintaining abilities gained during the hard training period. The easy period should still include regular athletic activity (2-3 days per week) but at a low volume. Then depending on the athlete and the situation, some form of strength training may need to be kept in for maintenance. For example, if we have a jumping athlete with an average strength level, he or she would likely want to do something to keep the quadriceps tendon strong during an easy period that lasts longer than a week. The exact exercises, timing, and duration depend on the athlete and the situation. I will refrain from attempting to give universal prescription.

- Lastly, don’t be afraid to take advantage of an opportunity to get long term rest. We don’t know how much overshoot happens in a given time period, but you can count on some shift toward faster twitch speed. Again this does not mean that you will be more athletic after not exercising for a month. The abilities you lose over that time may outweigh the fiber type changes. But you will be more fast twitch, and your body should be very fresh and ready to respond to training. So after a rest period you might be shocked at how quickly you can return to a high performance level and even surpass your previous abilities. With this in mind, taking a break at the end of the competitive season, for a vacation, or during a rehab period might be a good idea. Yes, you will likely come back less athletic if you rest completely for longer than a week, but it can actually help you in the long run.

The big fear that people have about an easy training period is losing the abilities that they gained. It's important to realize the athletic performance qualities are not as fragile as people tend to think. With regular athletic activity, coordination does not go anywhere. With reduction or cessation of strength training and more off days, explosiveness and elasticity actually improve. Flexibility is easily maintained. Strength is really the only thing you have to worry about losing. On that topic, consider the following points...

- Some times people can be shocked at how well they maintain strength just by doing regular athletic activity. I've seen examples of athletes who don't touch a weight for months and return to find that they are almost as strong as they were before. However this does not always happen.

- It is normal for someone doing an easy period to lose some max strength but gain athleticism. Yes, without heavy lifting your max squat will likely go down some, but a max squat involves neural drive and muscle tension that are never used during athletic movements. During an easy period the strength that you are actually able to use for sports may stay the same or even increase. What I like to do is use a power measure to clue me in to what is going on in the strength department. A power measure is a movement in between strength and speed. Loaded jumps and throws, olympic lift variants, or even standing vertical jump and broad jump are examples. So if I'm doing an easy period, and my hang power snatch and broad jump are staying high, I can be confident that I am not experiencing strength loss that is negatively effecting athleticism.

- After an easy period, maximum strength can typically be regained quickly, often within a month of lifting. In fact, because the body gets fresh during the easy period, you may find yourself blasting through your previous strength plateau relatively easily.

- All that being said, strength maintenance is definitely something that needs to be on your mind during a longer easy period. Some people need to do more in this area than others. Again I cannot speak to every situation here, but I would encourage you to explore how much you can cut down on strength training while still staying healthy and being successful athletically.

STILL MORE...

A long jumper I worked with provided more examples of the benefits of low training volume and rest. (1) When Dillon first started training with me he got fast results training just twice per week. (2) In the weeks leading up to the state track meet, he did very little training. We were trying to get him to bounce back from fatigue accumulated from high running volume in track practice. At state he hit a long jump personal record by 6 inches. It was 14 inches longer than what he was jumping in the second half of the season while fatigued. (3) After the state meet Dillon did not work out for 6 weeks straight. When he began training again, he returned to his highest max velocity ever within 12 days. Understand that he is fairly gifted genetically; I am not saying everyone should train exactly as he did. But acknowledge the principles and apply them to your situation. Here is a recap of a year of his training. Long Jump Case Study.Lastly check out this Instagram post on the training of triple jump world record holder, Jonathan Edwards.

DO LESS, MY FRIENDS!